Untangling South East Queensland's Public Transport

There are some great things about public transport in South East Queensland. And a number of opportunities for improvement. Read on for more on this.

I recently visited Brisbane and South East Queensland and came away both impressed while also pondering some key changes to make public transport even better in the region. Here goes with my take on things.

A bit of background

To kick off, here are some basic facts about the South East Queensland.

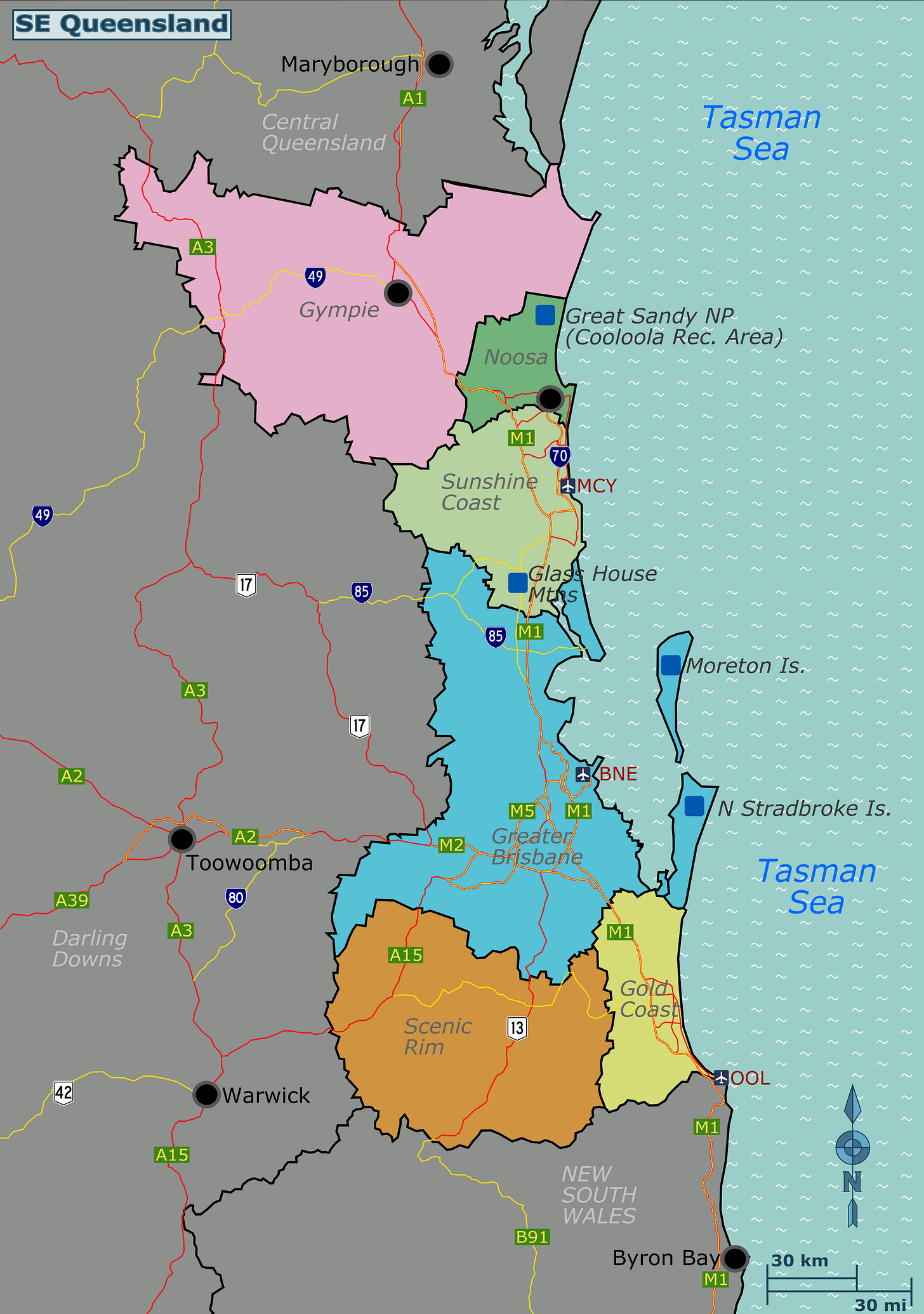

Firstly, South East Queensland is a huge semi-conurbated region of 35,248 square kilometres with 3.8 million people, making up three-quarters of Queensland’s population of 5.1 million. It includes Queensland's three largest cities: the capital city Brisbane, the Gold Coast and the Sunshine Coast. It is experiencing strong internal and international immigration with the regional population predicted to increase to 6 million by 2046.1 On top of this, the South East Queensland region needs to tee up significantly to host the Olympic Games in 2032.

Patronage recovery

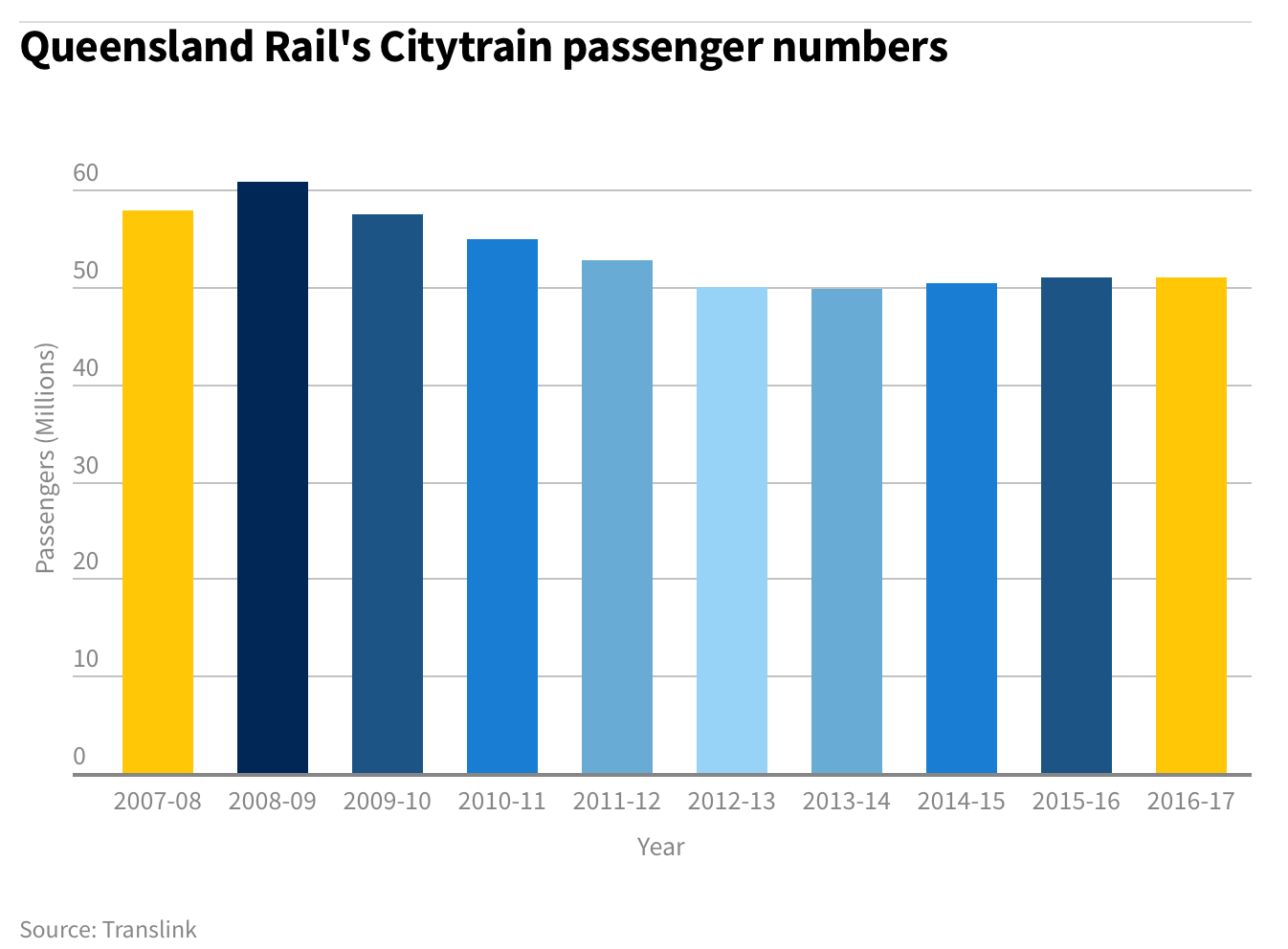

Even prior to the pandemic’s devastating impact on public transport, Brisbane and South East Queensland’s public transport system patronage was on the slide.

Passenger journeys were 153 million in 2022-23, about 81% of the 189 million trips taken in 2018-19, the last financial year before COVID hit2. This is in a typical range for post-pandemic patronage recovery but the raw figure conceals two things.

Firstly, patronage recovery has been uneven between the modes. Gold Coast Light Rail is running at 115 per cent of pre-pandemic levels while the Queensland Rail heavy rail network is sitting at about 78 per cent.

But that fact in itself conceals another fact. That rail patronage was already on a significant slide even before the pandemic took hold in early 2020. See below for more.

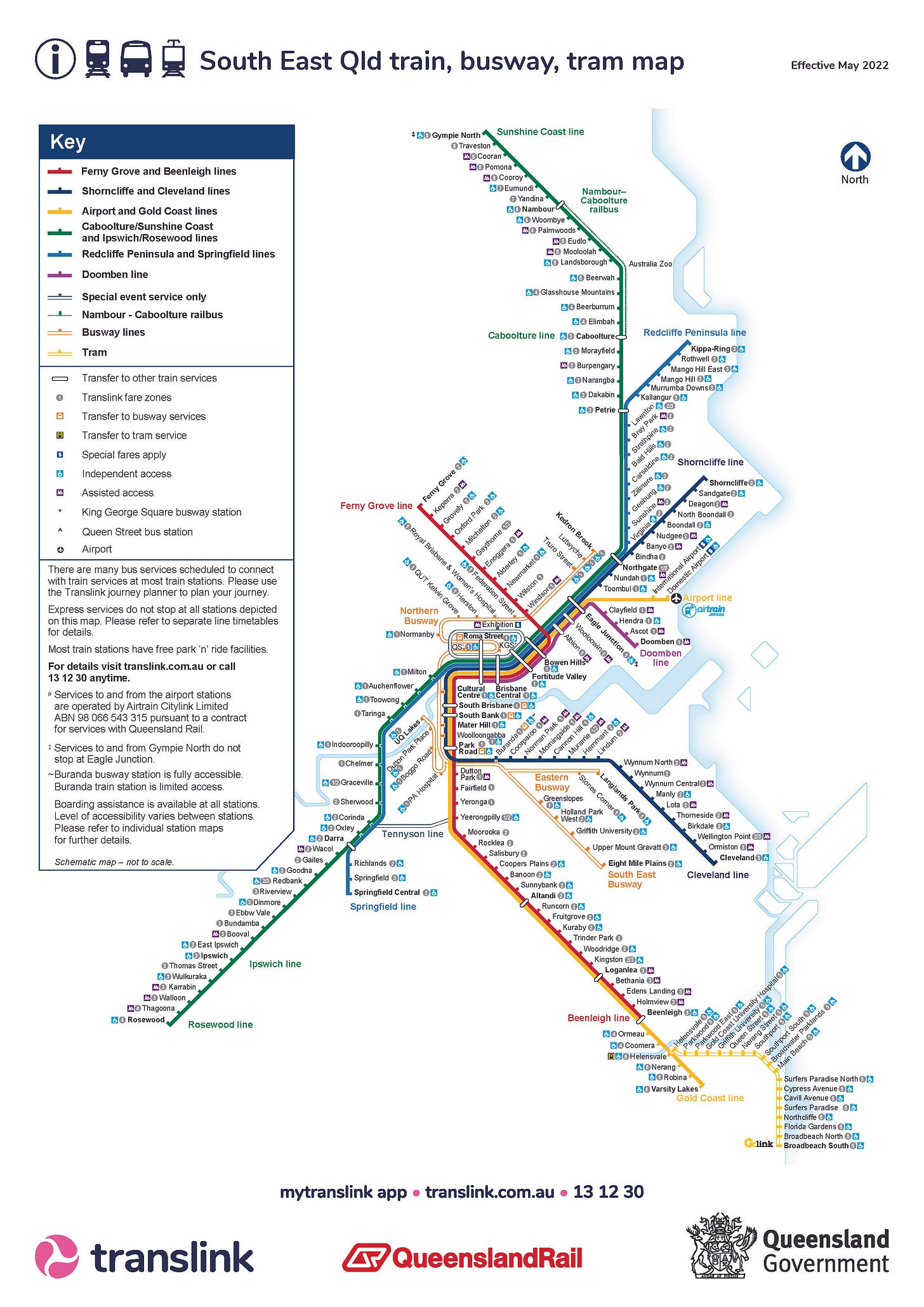

Big train network with big opportunities

Brisbane and South East Queensland has a big train network. It has 13 lines stretching over 689 kilometres serving 154 stations. In the 2022/2023 financial year, it carried 42.86 million passengers. As can be seen in the chart below, rail patronage has dropped by 30 per cent from 60.9 million in 2008/2009 to 42.86 million in 2022/ 20233. In the last full financial year prior to the pandemic, 2018-2019, there were 55 million rail trips on the South East Queensland network4

By way of comparison, Auckland’s rail network carried 11.9 million passengers on its 75 kilometre rail network in 2022/2023 (taking into account the closure of the 18 kilometre Papakura to Pukekohe section for electrification works). This means that the South East Queensland rail network carried 62,206 passengers per track kilometre/ year in 2022/2023 while Auckland’s rail network carried 95,867 passengers per track kilometre/ year.

There was a significant “Rail Fail” period where the improved rail timetable introduced with the opening of the Kippa-Ring Line in 2016 had to be abruptly withdrawn due to the lack of train crew to operate the timetable. The full planned 2016 timetable was only able to fully re-implemented three years later, in 2019.

Key features of the South East Queensland train network

Heavily focused on peak period commuting to Brisbane City Centre

Significant focus on commuter car parking at stations, including stations quite close to the city centre

Extensive triple and quadruple tracking on the inner parts of the network, including quadruple track through the city centre

But constrained by only two tracks on the Merivale rail bridge over the Brisbane River to the south and flat junctions around Roma Street Station

Generally only half-hour off-peak, evening and weekend train service on most lines (except on some inner lines which have 15 minute or better weekday frequency)

Very limited bus-rail integration within Brisbane city limits

As is typical of rail networks, longer-distance journeys focused on the city centre have been amongst the most heavily impacted by post-pandemic hybrid working patterns. The South East Queensland rail network has been impacted by this due to its strong orientation on peak commuting to Brisbane City Centre. But rail patronage is back to 78 percent of pre-pandemic levels and is continuing to improve.

Cross River Rail & SEQ Rail Connects

Similar to Auckland’s City Rail Link, Melbourne’s Metro Tunnel and Sydney City and South West Metro, Brisbane’s Cross River Rail aims to address core network constraints, particularly impacting accommodating growth in travel from the south. It is a new 10.2 kilometre rail line from Dutton Park to Bowen Hills, which includes 5.9 kilometres of twin tunnels under the Brisbane River and Brisbane City Centre. Of particular note, it includes a new underground station at Albert Street in the core of the city centre whereas the current Central and Roma Street stations are toward the edge of the city centre. The concurrent implementation of European Train Control System (ETCS) level 2 with Cross River Rail will enable optimisation of rail network capacity.

Network planning for the post Cross River Rail is detailed in the SEQ Rail Connect plan but can be boiled down to several key elements:

Sectorisation of the network so that each of the three new network sectors can run largely independently of the others

Focus on frequency on the urban network with “turn up and go” frequency and more standing room. This will be a significant improvement on the current often 30 minute interpeak, evening and weekend frequencies

Focus on seated capacity and speed on the longer distance journeys (Caboolture, Sunshine Coast, Gold Coast and Ipswich lines) with limited stops and express trains

Extending peak frequencies into the shoulder peak periods to spread demand and provide more travel choice

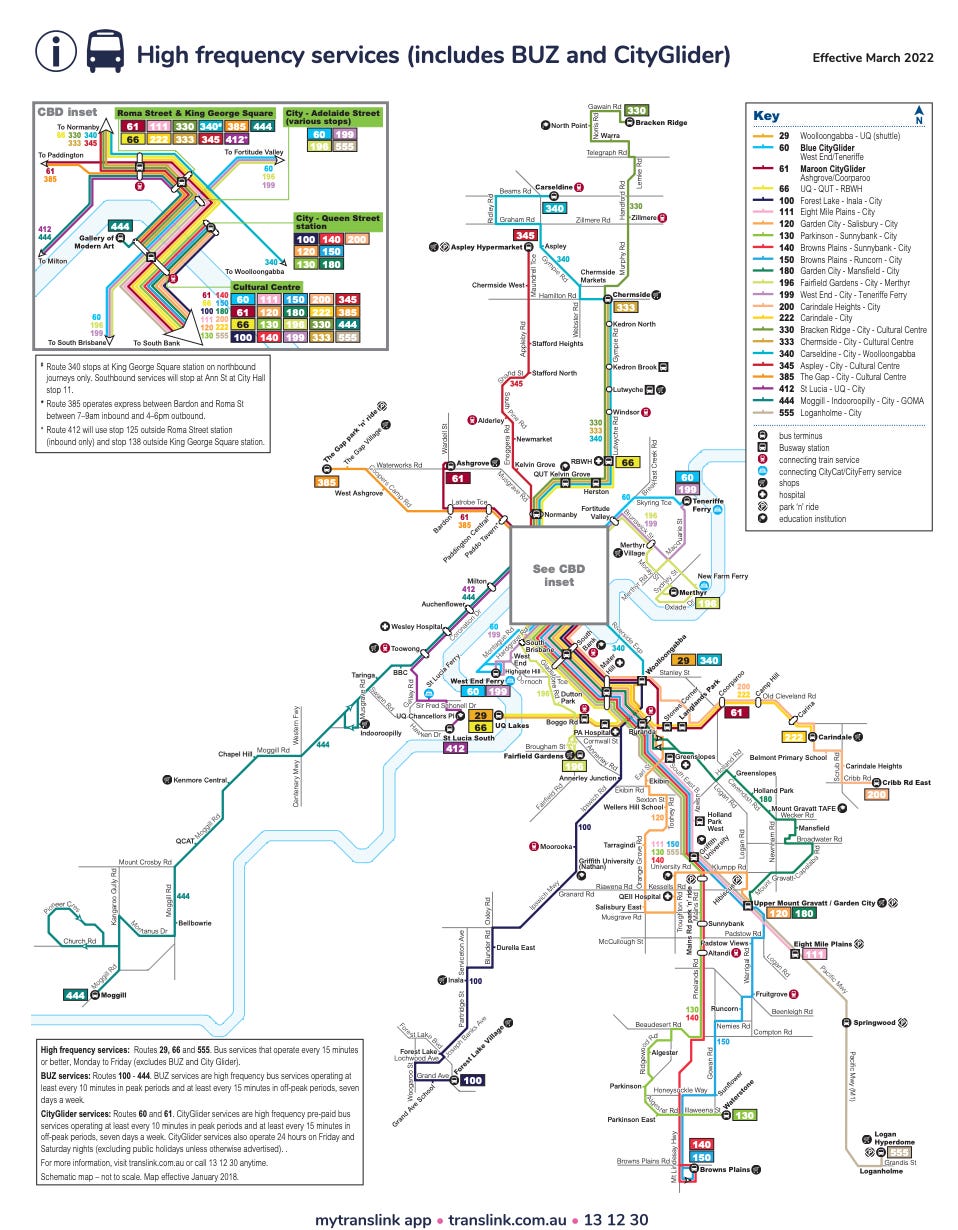

Brisbane’s bus network

There are a number of striking features of Brisbane’s bus network:

Extensive sections of fully-grade separated busways to the south east, east and north, including an underground bus tunnel in Brisbane City Centre

High quality urban design and place integration at busway stations which have strikingly better design and customer amenity than most Brisbane train stations

A busway operating model focused on one-seat ride bus routes fanning out from the busways at various points, all starting or passing through the city centre

A BUZ (Bus Upgrade Zone) network of high-frequency outer suburban bus services running limited stops, including only serving some busway stations, to and from the city centre. This network has driven significant patronage increases, particularly at weekends and non-peak periods

Limited cross-town bus service mostly passing through the City Centre

A bus network that runs independently from the rail network and not well integrated with it

As you can see from the frequent bus network map above, frequency alone doesn’t provide for simplicity and legibility. This is particularly obvious on the Southeastern Busway as it approaches Brisbane City Centre where numerous bus routes from numerous origins converge. This is further complicated by differing stopping patterns on the busways themselves. This means that only a few of the many busway bus routes stop at all busway stations. On top of this, the limited platform lengths at Buranda and Mater Hill stations lead to queuing of buses to get into their platforms.

This convergence of route is most obvious at the Cultural Centre Busway Station just south of the city centre. Due to the one-seat-ride network, there are many not fully utilised buses creating significant bus-on-bus congestion on the city centre approaches.

Overall, the Brisbane bus network is complex with additional services, such as the limited stops City Glider buses, overlaid on to the existing network. This network complexity is overlaid with stopping pattern complexity. For example, on the main road from Paddington towards the city centre, there are three bus routes, the 61 City Glider from Ashgrove to Stones Corner, the 375 Stafford City to Bardon and the 385 The Gap BUZ. Of these, only the 375 stops at all stops, while the 61 and 385 each have their own individual stopping patterns. This complexity is further exacerbated by the lack of on-board audio or visual stop announcements on buses.

Brisbane Metro - the bus that dares not speak its name

One of the measures being used to deal with congestion on the busways is the Brisbane Metro project. This project provides initially for two “Metro” services run by battery electric bi-articulated vehicles. Apparently, these are officially known as “Metro Vehicles” to avoid any association with the three-letter word “bus”, but these are in fact bi-articulated buses. One of these “buses that dares not speak its name” is in testing in Brisbane and by all accounts it provides excellent ride quality and a high quality of on-board passenger amenity. These buses will provide much needed core additional capacity on the south-eastern and inner northern busways.

But, and this is a big but, they simply replace two existing high-capacity frequent bus routes, the 66 and the 111, run by a mix of standard and articulated buses, with higher-capacity buses running more frequently. While there are some elements of bus network reform being implemented around Brisbane Metro, this is far from a full service review and largely leaves the existing city centre focused one-seat-ride network in place.

The key infrastructure elements of the $1.7 billion project are:

a 213 metre tunnel beneath Adelaide Street in the City Centre, connecting the Southeastern Busway to the Inner Northern Busway, bypassing the severely congested Queen Street underground bus station

upgraded Cultural Centre Busway Station

changes to Victoria Bridge to provide three lanes for bus buses, and dedicated cycling and pedestrian pathways

upgrades to some suburban busway stations including end of route vehicle charging facilities

a fleet of 60 battery electric bi-articulated buses

So while Brisbane Metro is a positive, it is not as positive as it could be due to it not being implemented concurrently with citywide bus network reform.

Gold Coast Public Transport

Meanwhile, the Gold Coast with a population of 640,7785, projected to grow to over a million people by 20466, is something of a role model integrated network of heavy rail, light rail and bus service meaning that the Gold Coast has one of the best structured networks in Australia. The centrepiece of this is Gold Coast Light Rail running every 7-8 minutes all day, every day, linking to heavy rail to Brisbane at Helensvale and running along the dense coastal strip as far as Broadbeach South, with an extension under construction to Burleigh Heads and a further extension planned to Gold Coast Airport and Coolangatta. It links numerous major destinations, such as Gold Coast University Hospital, Southport, Surfers Paradise and Broadbeach, supported by an intensity of non-city centre land use rarely seen elsewhere in Australia. Gold Coast Light Rail patronage is sitting at 115 per cent of pre-pandemic levels.

On the heavy rail front, the Gold Coast Line from Brisbane has received extensive investment since being rebuilt as a greenfields rail line from Beenleigh to Helensvale in 1996, and extended Nerang in 1997, Robina in 1998 and Varsity Lakes in 2009. Originally built as a single-track railway, the line was progressively duplicated with the final section between Coomera and Helensvale stations completed in 2018. The line south of Beenleigh is largely set up for 140 km/h running.

Investment in the line continues with three new infill stations being constructed in the Gold Coast at Pimpama, Hope Island and Merrimac as well as 20 kilometres of track quadruplication and straightening between Kuraby and Beenleigh (currently double-tracked). In addition, the corridor for the extension of the line from Varsity Lakes to Gold Coast Airport is protected for implementation in the longer-term.

Time-integrated east west bus services connect heavy rail to the dense coastal strip at all stations (as well as with light rail at Helensvale Station). From the current southern terminus of light rail at Broadbeach South, frequent all stops and limited stops buses continue further south to Burleigh, Palm Beach, Gold Coast Airport, Coolangatta and terminate just inside New South Wales at Tweed Heads.

The Central Gold Coast East-West Passenger Transport Study will identify preferred routes for high frequency east-west bus services in central Gold Coast, focusing on connections to and between the heavy and light rail lines.

Overall, the Gold Coast has one of the best structured public transport networks in Australia.

A tale of two coasts

While there has been extensive investment in heavy rail, light rail and bus service on the Gold Coast, the same cannot be said for the Sunshine Coast to the north. The Sunshine Coast has a population of 398,8407 and is projected to grow to over 500,000 people by 2041.8 In spite of this population, the densely populated Sunshine Coast coastal strip is not yet directly connected to the regional rapid transit network.

While the Gold Coast has a rapid transit spine running 7-8 minutes, the Sunshine Coast has only a single frequent bus route, the 600, running in mixed traffic between Caloundra and Maroochydore on the highly developed coast of the southern Sunshine Coast. A quality bus corridor was planned as part of the CoastConnect strategy in 2010 and the corridor protected for bus priority and bus queue jumps at key locations. But implementation is awaiting the outcome of the Sunshine Coast Direct Rail Line business case, the Sunshine Coast Public Transport Business Case (which in turn followed the Sunshine Coast Mass Transit Project) and is intended to contribute to the Southern Sunshine Coast Public Transport Strategy.

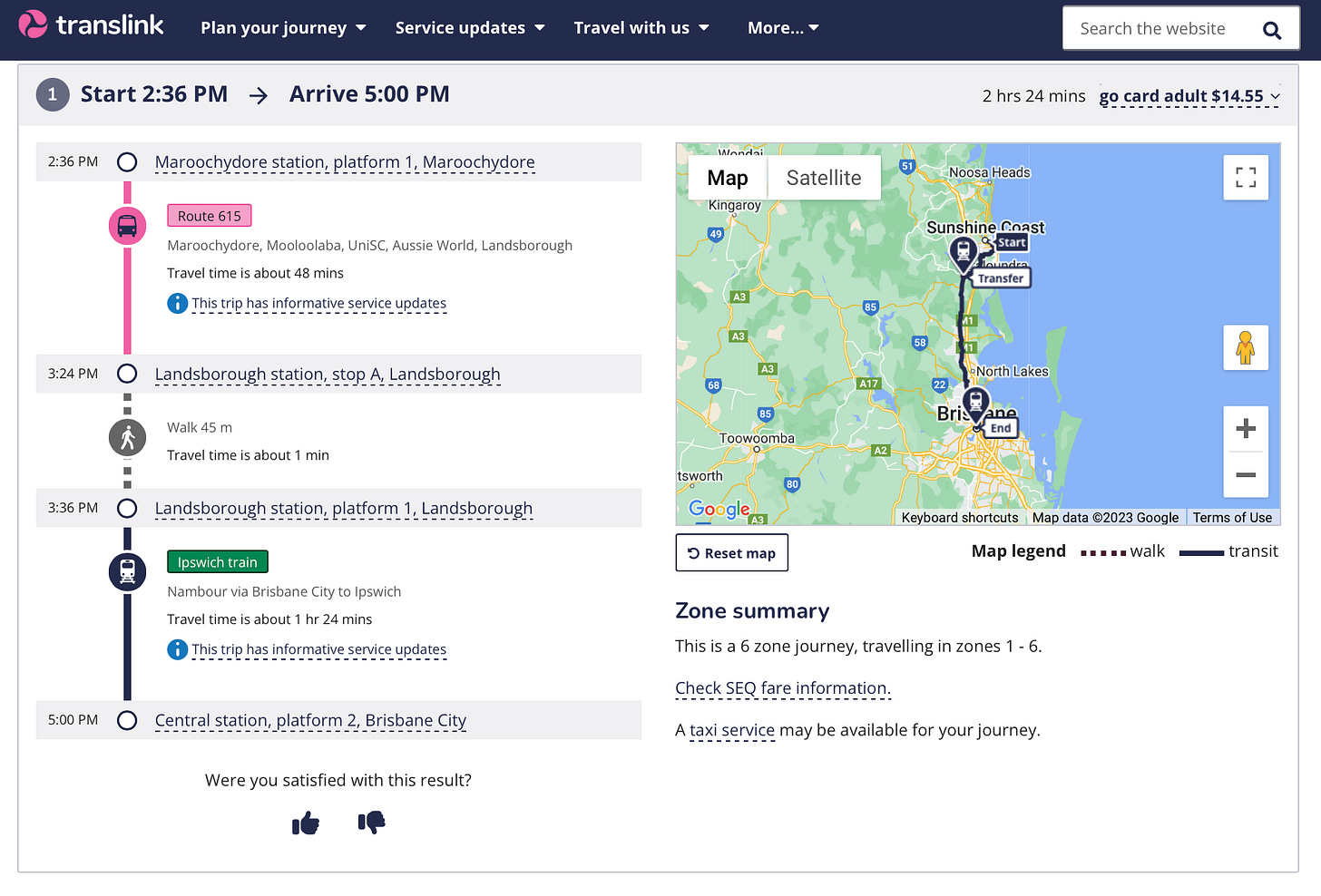

The situation with heavy rail is even worse as trains to the Sunshine Coast hinterland from Nambour only run to Brisbane every 90 minutes, requiring a lengthy connecting bus trip to and from the much more densely populated coastal strip. Currently the single track north of Beerburrum on a winding alignment with passing loops at stations severely limits train frequency and speed.

Plans have been afoot for a 37 kilometre rail connection from Beerwah on the existing Sunshine Coast rail line to Maroochydore, the centre for the Sunshine Coast, since around 1997, leading to the 2001 Caboolture to Maroochydore Corridor Study (CAMCOS) confirming corridor alignment and station locations. While the corridor is largely protected, it is only now in 2023 that detailed planning is underway, with $14 million in the 2023-24 Queensland state budget for a detailed business case expected to be completed in 2024.

At the same time, pre-construction work is underway on the much-delayed duplication and straightening of a 12 kilometre section of the existing Sunshine Coast Line between Beerburrum and Beerwah. This follows 13.7 kilometres of track duplication and realignment from Caboolture north to Beerburrum in 2009.

Frankly, there’s a lot of strategy and business case going on but not much action on the Sunshine Coast when compared to the Gold Coast.

CityCat ferries

Any piece on Brisbane's public transport network cannot ignore the minor and largely visitor-oriented CityCat ferry network. The serpentine nature of the Brisbane River makes them popular with visitors but not a time-competitive public transport options for other travellers, except where they provide cross river connections where no bridge crossing exists, such as between Bulimba and Teneriffe.

Final thoughts

There’s a lot of food for thought in how Brisbane and South East Queensland plans for public transport. The Gold Coast is a beacon for how integrated light rail, heavy rail and bus service can provide strong, well-structured networks where capacity and speed is focused on the areas of highest demand. The Sunshine Coast seems to be the Cinderella that is often invited late, if at all, to the public funding ball. This is a significant challenge at the 2032 Olympics will be held across South East Queensland, including the Sunshine Coast. There is already chronic peak and weekend congestion on the Bruce Highway from Brisbane to the Sunshine Coast and urgent needs for the Sunshine Coast denser coastal strip to be directly connected to the rapid transit network. And Brisbane has its ups and down. A lot of fully-grade separated busways, high-quality outer suburban service and a lot of service overall. But poorly integrated between buses and trains and overly complex and it is sometimes difficult to “get the hang” of the network.

But overall, some cause for optimism as Brisbane Metro will make a positive difference to the core of Brisbane’s Busway, Cross River Rail and SEQ Rail Connect will make for a stronger, more passenger-friendly rail network and the ongoing extension of Gold Coast Light Rail will make for an even stronger public transport spine. Just needs the Sunshine Coast to join the public transport investment party.

South East Queensland is Growing, Ministerial Statement, 31 July 2023

Gold Coast, Australian Bureau of Statistics website

Queensland Government population projections, 2023 edition

Regional Population, Australia Bureau of Statistics website

Population Growth, Sunshine Coast Council website

Nice article.

I visited SEQ earlier this month and was pretty impressed with the network, especially in the Gold Coast. I didn't do a lot of peak time travelling in Brisbane, but was pretty happy with the speed and reliability of the bus network, and found it easy to get around - the improvements to the cycle network around + across the river are really nice too. Do find it perplexing that they've chosen to use the Definitely-Not-Buses for the Brisbane "Metro", considering how successful the light rail is in GC - I wonder what the reasoning is for that?