LA Derailed?

30 years ago, LA starting rebuilding its rail system from scratch. While investment continues, ridership is down 60%. What went wrong? And what is the way forward?

Los Angeles famously had one of the world’s most extensive urban rail systems, in the form of red and yellow cars, until it was systematically dismantled in the middle of the 20th Century. But from the 1990s onwards, its urban rail network has been progressively rebuilt at vast expense but is still a shadow of its former self.

But ridership never matched earlier, perhaps inflated, expectations and the pandemic has hit LA’s rail systems hard, with ridership sitting at around 40% of pre-pandemic levels.

The Rise and Fall of Metrolink

To kick off, it’s good to go backwards before we go forwards.

The first move to rebuild rail in Los Angeles was the first stage of Metrolink, the commuter rail network for the Southland, including Los Angeles & Orange counties and the Inland Empire of Riverside and San Bernardino counties. The original three lines - San Bernardino, Ventura County and Santa Clarita - opened in 1992 have subsequently been expanded and extended to the current eight lines and 880 kilometres of track.

Average ridership weekday ridership peaked at 42,928 as of 2017. And as is typical of many U.S. transit systems toppling off the edge of a fiscal cliff at present, ridership in the final quarter of 2022 was just 15,100 per weekday.

To give a sense of just how bad this is, consider this:

Each kilometre of LA’s commuter rail network has a total of 17 weekday trips

The five counties that Metrolink serves have a total population of 18,491,895

This means that weekday commuter rail ridership = 0.00082% of population

So how does LA manage to do so badly with commuter rail? A few reasons:

Enduring car-based culture, infrastructure and minimum parking requirements that reinforce car dependency as the only ‘legitimate’ choice

Consequently, station access is focused on park and ride, where a car is effectively required to access public transport. I call this COT - Car Oriented Transit

The pandemic response of increasing work from home, especially for people with very long commutes

In spite of this, a commuter rail model heavily focused on peak commuting to Downtown Los Angeles and not on all-day, every day travel for a whole range of purposes

An example of the previous point is the following.

The Ventura County Line opened on 26th October 1992. Over 30 years later, on 1st July 2023, it finally got weekend train service, in the form of two weekend round trips. To say that commuter rail in Los Angeles is a long way from a European-style S-Bahn/ RER or even a Toronto Regional Express Rail model of regular all-day, every-day service, is quite the understatement.

Meanwhile, in LA County…

It’s a bit of a different story in Los Angeles County but the current state is similar to that of the Metrolink commuter rail network.

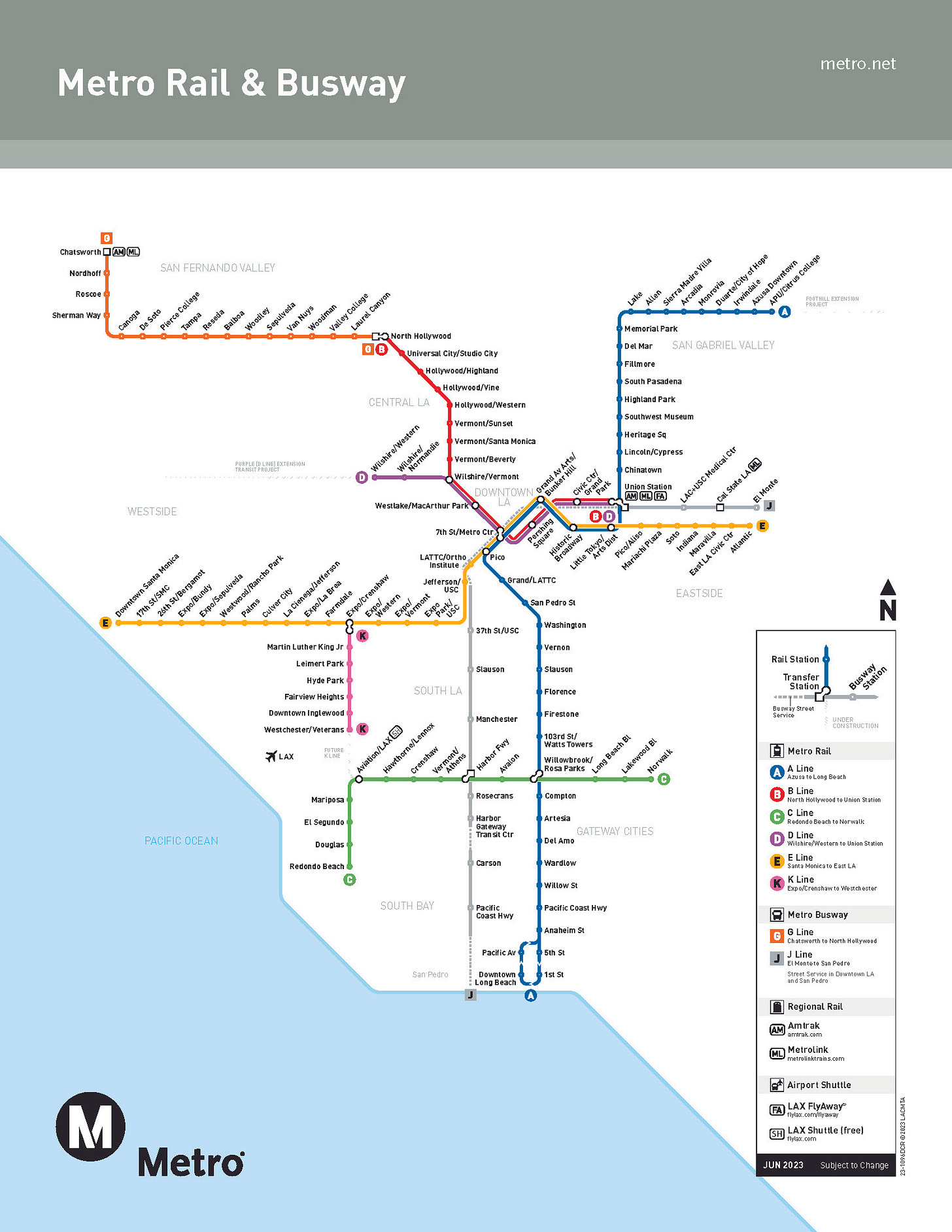

The LA Metro rail network, ironically often built on abandoned red car rail corridors, is shown below (including busways of variable quality):

A few striking things about the Metro Rail network

Firstly, much, but by no means all, of the network is actually pretty useful and links quite a number of key destinations such as Santa Monica, Long Beach, Hollywood and Pasadena, to Downtown Los Angeles and each other. Other parts of the network, such as the 31.4 kilometre C Line light metro, which famously goes from nowhere to nowhere via nowhere, struggle to find a purpose. Even so, it’s the fastest line in the Metro Rail network at an average speed, including station stops, of 55 km/h and at its peak carried 13,499,453 passengers in 2013. This declined by 60% to 5,390,229 in 2022, but it still carried more people in 2022 than the entire 880-kilometre commuter rail network.

For many years the Blue Line light rail, now rebranded as the A line, was the poster child of the network. Operating to Downtown LA from Long Beach via the often deprived communities of South Los Angeles, it carried 28,959,483 passengers in 2012 and often struggled to keep up with demand with three-car trains and narrow platforms. The pandemic solved that issue by leading to a 63% reduction in demand to 10,663,617 in 2022.

Connecting the core

So while ridership has slumped since the mid-2010s and plummeted in the wake of the pandemic, there is continued investment in the network, some of it actually useful. A key move is the Regional Connector which opened on 16th June 2023.

This provides a second rapid transit route through Downtown Los Angeles but, much more importantly, connects the former four-line light rail network (Blue, Gold x 2 branches, Expo) into two through-routed light rail lines, one east-west (E Line) and one north-south (A line), with both lines serving all of Downtown Los Angeles. This is a game changer in terms of connectivity and minimising unnecessary connections.

It has also created possibly the world’s longest light rail at 79.7 kilometres from Long Beach via Downtown Los Angeles to APU/ Citrus College in the San Gabriel Valley. It takes two hours to run end-to-end at an average speed of 39 km/h. And it is being currently being extended by 18.2 kilometres to Pomona, with a subsequent as yet unfunded 15 kilometre extension to Montclair. If that extension eventuates, the total line length would be 112 kilometres.

Speed matters in a very spread out city

While the A line’s sheer length is a fun fact, less fun is that, unlike the B, C & D lines, the A, E and K light rail lines are far from being fully grade-separated and are subject to significant delay at signalised intersections. The worst impact is on the E line west of Downtown Los Angeles. This leads to an average travel speed of just 31 km/h, rivalling Auckland’s Western Line for taking the rapid out of rapid transit, making rail travel times between Santa Monica and Downtown LA uncompetitive with the chronic all-day congestion on the Santa Monica Freeway. These are some of the numerous examples where LA’s rail investments have been over-specced, often in unnecessary tunnel section due to community opposition, or under-specced in terms of at-grade signalised intersections without signal priority for light rail.

Going West on Wilshire

On a more positive note, the fully grade-separated D line subway is being extended in stages west underground further along Wilshire Boulevard towards Beverly Hills, Century City and Westwood, home to UCLA. This route is served by the flagship Metro Rapid bus route 720 along a continuous dense corridor linking a large number of major trip attractors from Rodeo Drive to Miracle Mile and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

The original section of the line was opened to its truncated terminus at Western Avenue in Koreatown in 1996. (For the full story on this, know as the La Brea Tar Pits saga and the full history of LA’s metro rail network development, I highly recommend reading Ethan Elkind’s fascinating book Railtown: The Fight for the Los Angeles Metro Rail and the Future of the City). The extension west to UCLA and beyond will enable enormous increases in travel speed and mobility for public transport customers on Wilshire west of Western Ave. Wilshire Boulevard buses carried over 55,000 passengers per day in 20151 which made it the busiest bus corridor in Los Angeles and one of the busiest in the United States. This is one case where there is good integration between public transport investment and more supportive land use.

Heading towards LAX

The other new investment is the recently completed first 9.5 kilometre stage of the K Line light rail from Expo/ Crenshaw to Westchester/ Veterans which opened on 7th October, 2022. The genesis of the line was as a response after the 1992 LA Riots to address transport equity in South Los Angeles. The fact that it took 30 years to implement the first stage of the line is somewhat telling about the speed of that response. Current daily ridership as of May 2023 is a somewhat modest 2,048. It will become quite a bit more useful when it is extended in 2024 to LAX/ Metro Transit Center, where it will connect by an automated people mover to all of LAX’s terminals. As well, it will connect to the C Line and take over the C Line branch to Redondo Beach. Total project cost is $US2.1 billion.

So while there’s a lot going on with Metro Rail in Los Angeles in terms of network development, the ridership story is not good news. Post-pandemic ridership recovery has been a mixed bag across the planet but quite a number of cities (e.g. Vancouver, Brisbane, Auckland, Wellington) have recovered most of the pandemic ridership loss while others (Perth, Dunedin, Gold Coast) have fully recovered. Yet the United States in general and Los Angeles in particular have a long way to go with ridership around 40% of pre-pandemic levels. And even before the pandemic most US cities, with some worthy exceptions such as Seattle and Houston, were already bleeding ridership.

Safety is a real issue in LA

Widespread reporting of open drug use on Metro’s trains, as per this Los Angeles Time article, “L.A. riders bail on Metro trains amid ‘horror’ of deadly drug overdoses, crime” certainly doesn’t help the matter, reinforced by frequent reports of similar experiences by public transport customers.

As with many public transport systems in the United States, the role of law enforcement in Los Angeles is all too often to act as the interface between the public transport system and the intertwined problems of homelessness and addiction in a city where by and large there is no ambulance at the bottom of the cliff. The 2023 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count results showed a 9% rise in homelessness on any given night in Los Angeles County to an estimated 75,518 people. With fare capping now in place on Los Angeles Metro buses and trains, public transport itself has become the nearest thing to affordable housing for the unhoused, quite a number of whom are veterans suffering from PTSD after fighting for the United States in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Final thoughts

The lesson from Los Angeles, and across the United States, is at least partly clear. “Build it and they will come” may have worked in the Field of Dreams but it only works in reality if the public transport system provides all of the key elements of frequency, connectivity, reliability, some semblance of speed, a long span of service and probably most important of all a safe and inclusive experience for all members of the community. Public transport in Los Angeles has a long way back to be the mode of choice by the 2028 Olympics but will only get there if it addresses all of these fundamental issues.

The Long Haul: A Comparative Performance Analysis of Bus and Rail Transit in Los Angeles, page 8