Canada's regional and rural public transport problem

While Canada's largest cities are investing heavily in public transport, regional and rural public transport is going nowhere fast. Case study: British Columbia's Lower Mainland and Sea to Sky Highway

If the United States is looking to solve its post-pandemic urban public transport malaise, including the fiscal cliff many US transit agencies are facing, it should look north of the 49th parallel to Canada, where Vancouver, Montréal, Toronto, Edmonton and Calgary are all investing heavily in transit infrastructure and service. And in fact Metro Vancouver is widely regarded as something of a role mode of public transport development and transit oriented development.

The decline and fall of rural bus service

But sadly, outside of the Québec City to Windsor corridor in parts of Québec and Ontario, served by semi-regular and semi-fast Via Rail trains, and the emerging European style regional rail network in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton area, the same cannot be said for regional and rural public transport in the rest of Canada. Key anti-milestones in this process included the withdrawal by Greyhound Canada of all services in Western Canada in 2021, and the withdrawal of remaining Canadian domestic services in Ontario and Québec in 2021. It remains to be seen if FlixBus’s acquisition of Greyhound will see reinstatement of any of its former Canadian inter-city bus service.

Even worse was the situation in Saskatchewan. The Saskatchewan Transportation Company was a crown corporation with “a mandate to provide service between major urban centres and to as much of the rural population as possible”1 The company was shut down and its assets sold by the provincial government in 2017, leaving much of rural and regional Saskatchewan overnight without public transport service.

The near-total absence of rural public transport, effectively makes hitch-hiking (paid or unpaid), the only viable transport option for many. This was, and remains, a factor in the Canadian crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Children. For example, “The Highway of Tears is a 719-kilometre (447 mi) corridor of Highway 16 between Prince George and Prince Rupert in British Columbia, Canada, which has been the location of crimes against many Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) beginning in 19702.”

Canada’s rural and regional public transport crisis also manifests itself in the regional hinterlands of many of its largest cities - with the Greater Toronto and Hamilton region’s extensive efforts to create frequent all-day, bi-directional rail service being a standout for emulating a European regional rail model in North America as a worthy exception.

Where regional boundaries determine transit access

British Columbia is no exception to this regional transit crisis. Public transport planning in British Columbia is split between Translink for Metro Vancouver and BC Transit for the remainder of the province. While Translink is an exemplary public transport agency well deserving of more attention for its service within Metro Vancouver, the region’s breath-taking housing unaffordability has caused people to live further afield in the Fraser Valley and along the Sea to Sky Highway between Vancouver, Squamish and Whistler. But public transport responsibilities come up against regional boundaries and create voids in public transport service, literally driving people to drive long distances due to the near absence of other choices.

Fraser Valley

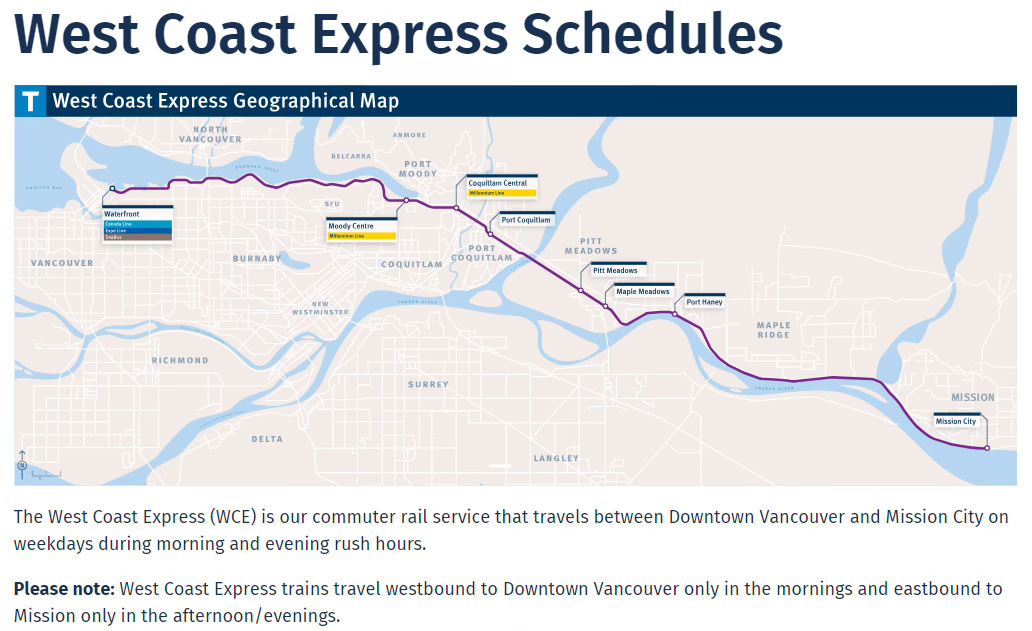

An example of this is the Fraser Valley in British Columbia’s Lower Mainland. Current public transport connections are the West Coast Express, a classic North American commuter rail model, of peak-only, peak-direction service towards Vancouver city centre in the morning peak and back to Mission in the afternoon peak. It harks back to a bygone era where work schedules were rigid with predictable tidal flows of commuters heading to work in downtown office towers in the morning and returning in the late afternoon. It provides no interpeak, evening, weekend or public holiday service, thereby complete failing to reflect the diversity of needs that all-day, every day public transport can serve.

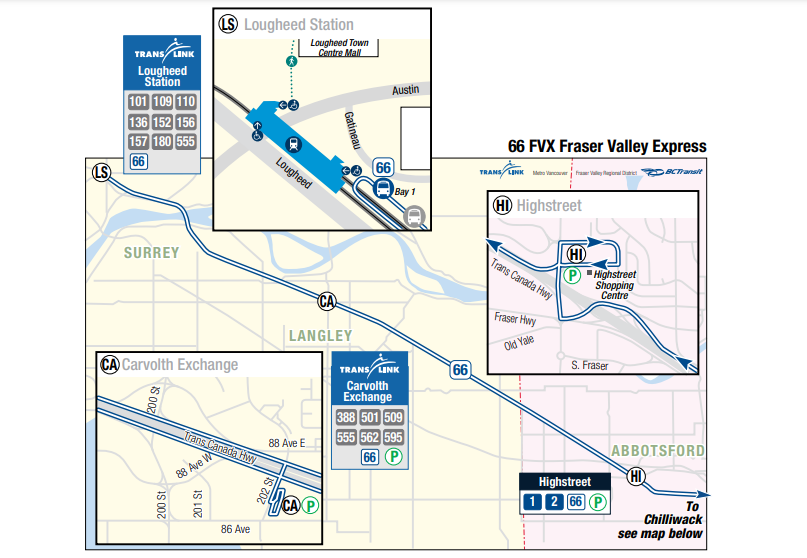

In addition to the West Coast Express peak-only service, there is some all-day bus service provided by BC Transit’s Fraser Valley Express (FVX) between Chilliwack, Abbotsford and connecting to the Vancouver SkyTrain network at Lougheed Station. It runs roughly hourly weekday daytimes, every hour and a quarter on Saturdays and every hour and a half on Sundays. But it doesn’t serve Downtown Abbotsford, such as it is, nor Mission and only has very limited stops en route. The end to end run time from Chilliwack to Downtown Vancouver is around two-and-a-half hours, roughly an hour longer than driving the same route.

There is no temporal, spatial or fare integration between West Coast Express and the Fraser Valley Express. West Coast Express accepts Compass Card, credit and debit cards, Apple and Google pay and Interac (NZ/AU= EFTPOS). For Fraser Valley Express, single rides are exact fare cash only (whatever that is!), with no change given or Umo card. And there is no fare integration between FVX and SkyTrain for travel into Vancouver.

So, the 324,005 residents of the Fraser Valley Regional District have the choice of driving the Trans Canada Highway or the use of two disjointed and very partial public transport alternatives to access work, healthcare, retail and leisure opportunities in Metro Vancouver.

Sea to Sky Highway

Similar issues exist in the Sea to Sky Highway corridor between Vancouver, Squamish and Whistler in the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District. As with the Fraser Valley, Vancouver’s housing supply and affordability crisis has pushed people up the Sea to Sky Highway, especially to Squamish. The Sea to Sky Highway was extensively upgraded in the lead-up to the 2010 Winter Olympics but the parallel rail corridor was untouched and is only used by occasional tourist-oriented trains operated by Rocky Mountaineer. While this is undoubtedly a stunning visitor experience, the minimum price tag of $A4,509 and very infrequent operation puts it clearly out of the ballpark of having any public transport function for the corridor.

Bus service does exist in the corridor but is very limited and focused on travel to Whistler for skiing and other visitor activities. As such, it is infrequent, highly seasonal and often focused on journeys to and from YVR Vancouver International Airport. Some trips make no stops en route between YVR and Whistler and only one of the two operators even stops in Squamish. There are no services that work around typical working day schedules. Prices are around $40 for a return trip.

Conclusion

For different reasons, the existing public transport offers between the Fraser Valley and the Sea to Sky Highway corridor to and from Metro Vancouver are very far from being frequent, reliable, all-day every day connections. But local advocacy group Mountain Valley Express has a vision for how a five line regional rail network, including high-speed rail to the United States, could form the cornerstone for inter-regional mobility in the Lower Mainland of British Columbia and beyond.

This is a certainly a very ambitious programme but one with significant engineering and planning smarts that sits behind it. I highly recommend diving into the vision document to get a sense of the scale of ambition and what would be needed to get this all to happen. This is the sort of long-term thinking that public agencies should be doing in the midst of a climate crisis as business as usual, but sadly that thinking seems to be in sadly short supply outside of Metro Vancouver in British Columbia. In the meantime, surely there are good incremental steps that would help set the stage for the longer-term vision - such as all-day, every-day service on the West Coast Express, its extension to Chilliwack as well as some actual conventional public transport service on the Sea to Sky corridor.

Saskatchewan Transportation Company on Wikipedia

Highway of Tears on Wikipedia