The Rio Olympics Public Transport Legacy

Much ink was spilt in the lead-up to the Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro on a range of organisational deficiencies around the games. While this is an Olympic staple - bored sports journalists drumming up stories in advance of the kick-off about whether the host city is in fact ready for the event - the coverage has been particularly virulent around the 2016 Summer Olympics.

One central tenet of this coverage has been the purported focus on public transport investment in the relatively affluent Zona Sul (South Zone) of the city to the detriment of the much poorer Zona Norte (North Zone) and Zona Oeste (West Zone). This narrative focuses on the Olympic legacy being conflated with Line 4 of the Metrô do Rio (Rio Metro) from Ipanema to Barra de Tijuca, a fast growing affluent part of the city.

But does this hype about the undoubted inequalities in Rio de Janeiro being mirrored in the transport investment for the games and the 2014 World Cup match the reality? Unlike most non-Brazilian sports journalists, I speak Portuguese so I thought I would dig a little deeper into this question.

But to kick off, here's a quick primer on Rio de Janeiro's public transport system. The ridership backbone of the system, as in most cities, is the humble bus, operated under the umbrella of Rio Ônibus, whose four constituent private consortia are contracted by the city to provide bus service. And the backbone of this backbone is the so-called Quentão (big hottie) non-air-conditioned bus - pictured below.

Typical Rio de Janeiro Quentão bus. By court degree all buses have to be air-conditioned by December 2016 but it remains to be seen if all of Rio's 8,266 buses are air-conditioned by this date. Photo credit: Guilherme Pinto

The 440 municipal bus lines carry 6,671,000 passengers daily or roughly two billion trips annually. 29.52% of all main mode trips in Rio de Janeiro are on municipal buses, with an additional 7.88% (1,781,000 passengers) on intermunicipal buses.

The Metrô do Rio (Rio Metro) carries 625,205 passengers daily or 228.2 million annual trips on a 58 kilometre network. The Metro is the main mode for 2.94% of trips.

Metrô do Rio train. Photo credit: Mario Roberto Duran Ortiz. Creative Commons 3.0 licence.

Supervia is the commuter rail network connecting Rio de Janeiro to the outlying communities of the Baixada Fluminense. It carries 620,000 passengers daily or 152 million annual trips on a 252 kilometre network. 2.51% of main mode trips are by commuter rail.

Supervia train. Photo credit: Clarice Castro. Creative Commons 2.0 licence.

Ferries, operated by CCR Barcas, provide transport to Niterói as well as to the island of Paquetá and Cocotá on the Ilha do Governador. They carry 105,000 passengers per day or 29 million annual rides. 0.46% of main mode trips are by ferry.

Estação das Barcas, Niterói. Photo credit: Rafael Max. Creative Commons 3.0 licence.

Now back to the reason for this post: What was promised in public transport investment for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Summer Olympics? What was actually delivered? And what difference did it make to the mobility of the average Carioca (resident of Rio)?

Rio de Janeiro Rapid Transit Network. Map source: Maximilian Dörrbecker. Creative Commons 2.0 licence.

There were six major public transport projects intended to be delivered as part of the legacy public transport infrastructure for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Summer Olympics with an extensive Bus Rapid Transit network, known as the High Performance Transportation Ring, made up of four corridors at its core, covering 150 route-kilometres and able to transport 1.7 million daily passengers. These projects are:

Metrô Line 4.

TransCarioca BRT.

TransBrasil BRT.

TransOlímpica BRT.

TransOeste BRT.

Light rail network.

Metrô Line 4 links estação General Osório, in Ipanema in the Zona Sul (South Zone) (where it connects with Line 1 of the Metrô), to estação Jardim Oceânico in Barra da Tijuca in the Zona Oeste (West Zone) of the city. It opened on the 30th of July 2016 for Olympic-related travel only and is scheduled to open to the public only after the completion of the Paralympic Games on the 17th of September 2016. In future, it is planned to extend the line eastward to the city centre with intermediate stations in Jardim Botânico, Humaitá and Laranjeiras and westward to Recreio dos Bandeirantes. It cost R$ 8.5 billion ($US2.66 billion) to construct.

The four Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) corridors below each either run or are planned to run in dedicated right-of-ways separated from traffic with a pattern of all-stops and express services fed by a extensive network of feeder buses. Fares are pre-paid off board through the use of smart cards.

TransCarioca BRT runs between Terminal Alvorada in Barra da Tijuca and the international airport in Galeão. Its route covers 39 kilometres with 45 stations. It opened just before the World Cup in 2014 and carries 230,000 passenger per day. End-to-end public transport travel times dropped by 60%. It cost R$ 1.833 billion ($US574 million) to construct.

TransBrasil BRT began construction in 2015 and is planned to connect Deodoro via Avenida Brasil with the city centre and onwards to Santos Dumont Airport with 28 stations. Its estimated budget is R$1.3 billion ($US407 million).

TransOlímpica BRT links Barra da Tijuca and Recreio dos Bandeirantes to Magalhães Bastos and Deodoro covering 26km with 18 stations. It opened on the 9th of July 2016 for Olympic-related travel only and is scheduled to open to the public after the Olympics on the 22nd of August 2016. It cost R$2.2 billion ($US689 million) to construct.

TransOeste BRT links estação Jardim Oceânico in Barra da Tijuca (where it connects to Line 4 of the Metro) to Santa Cruz and Campo Grande. It opened in 2012 and carries 200,000 passengers per day. End-to-end public transport travel times were reduced by 50 per cent - and a whopping 65 per cent for the express service pattern - with an average trip reduction of 40 minutes per passenger. At peak, it is carrying 17,000 passengers per hour, above its design maximum of 15,000 passengers per hour and is struggling with capacity issues at peak times. It cost R$900 million ($US282 million) to construct.

The Light Rail Network's first stage opened on the 5th of June 2016. Its primary function is internal circulation in the city centre, linking the Zona Portuária (Port Zone), financial district and cultural corridor, and to connect the various transport terminals - Santos Dumont Airport, the ferry terminal at Praça XV, the Central do Brasil commuter rail station and the Rodovíaria Novo Rio intermunicipal and interstate bus terminal - to one another and to the Rio Metro. It cost R$ 1.167 billion ($US365 million) to construct.

Inaugural run of Rio de Janeiro's LRT system. Photo credit: Fernando Frazão/Agência Brasil. Creative Commons 3.0 licence.

Complexo do Alemão gondola

While not directly a World Cup or Olympics legacy project, the Complexo do Alemão gondola, modelled on Metrocable in Medellín, is noteworthy as an attempt to integrate a favela into the wider city.

The Complexo do Alemão favela - in reality a compilation of many favelas - had a population of 69,143 at the 2010 Census and a Human Development Index that was the lowest of any neighbourhood in Rio de Janeiro. In late 2010, control was wrested from drug dealers when the police and army invaded the favela and "pacified" it.

The gondola opened for service on 8th of June 2011. It is 3.5 kilometres long, has six stations and links at its Bonsucesso terminus to the Supervia commuter rail network. Favela residents are entitled to two free daily trips on the gondola. It cost R$210 million ($US 66 million) to construct.

Complexo do Alemão gondola: Photo credit: Mario Roberto Durán Ortiz. Creative Commons 3.0 licence.

In terms of overall mobility, the High Performance Transportation Ring and other World Cup and Olympics legacy public transport investments will, when all projects including the under construction TransBrasil BRT project are complete, increase the proportion of Rio's residents with access to rapid transit from 18% to 63%.

World Cup and Olympics legacy public transport investments will ...increase the proportion of Rio's residents with access to rapid transit from 18% to 63%.

While much of the BRT network hubs around affluent Barra de Tijuca, its predominant service area are in the poorer Zona Norte (North Zone) and Zona Oeste (West Zone) of the city, where they have led to very significant reductions in public transport travel times over pre-existing on-street bus services operating in mixed traffic.

The minimum wage in the state of Rio de Janeiro starts at R$ 1,052.34 ($US330) per month for domestic and unskilled workers. An integrated fare within Rio de Janeiro city limits is R$3.80 ($US1.19) with one transfer and for services crossing city limits, the fare is R$6.50 ($US2.04), also with one transfer. For 21 working days per month, commuting to and from work within city limits costs R$159.60 (15.1% of minimum wage) and R$273 for trips crossing city limits or 26% of the minimum wage. Fortunately, under Brazilian labour law, it is the employer's responsibility - with some exceptions - to meet the costs of their employees' public transport travel. This is known as the Vale-transporte. However, public transport affordability remains a significant challenge for people not in employment. While Rio's complex system of public transport smart cards offer discounts for journeys involving connections, they are not true integrated fares.

Main trip mode share for weekday trips in Rio de Janeiro: Source: Plano Diretor da Regiao Metropolitana do Rio de Janeiro

Public transport operations are not subsidised in Rio de Janeiro although fares are regulated by the public sector. For example, when the Flumitrens commuter rail was privatised in 1998, the rights to operate the service were auctioned. The successful bidder, Supervia, paid the Rio de Janeiro state government R$30 million and undertook to invest a further R$250 million of its own funds in service and infrastructure improvements. Similarly, bus services are unsubsidised and in fact the four consortia making up Rio Ônibus collectively made R$70 million in profit in 2013.

While there is public sector capital expenditure on public transport, this principally benefits rail and bus rapid transit projects, with some relatively limited investment in bus lanes on major arterial bus routes, for example in Copacabana, Ipanema and the city centre.

Of significance is the complete dominance of the bus mode making up 42.82 per cent of all main mode journeys with rail modes - Metro and commuter rail - making up just 5.45 per cent of such journeys. Public transport in total, including ferries, makes up 48.76 per cent of all trips, dwarfing the private motorised mode share of 19.47 per cent.

Of the six key public transport projects, two - TransCarioca and TransOeste - have been in service since at least 2014. The light rail network has only been in service since June 2016 and two projects - Metro Line 4 and TransOlímpica - will only enter public service after the Olympic games. One project - TransBrasil - is still under construction. Clearly delivering and opening all six projects to passenger service prior to the Olympics did not happen.

Early evidence from the BRT projects is that they have delivered considerable travel time benefits to bus customers. In the case of TransOeste, this equals 14 full days in travel time savings for an annual commuter. However, they have been less successful at achieving mode shift. A survey of TransOeste customers carried out showed that 84.6 per cent of customers formerly used conventional buses; 6.8 per cent used jitneys and just 2.4 per cent were former car drivers.

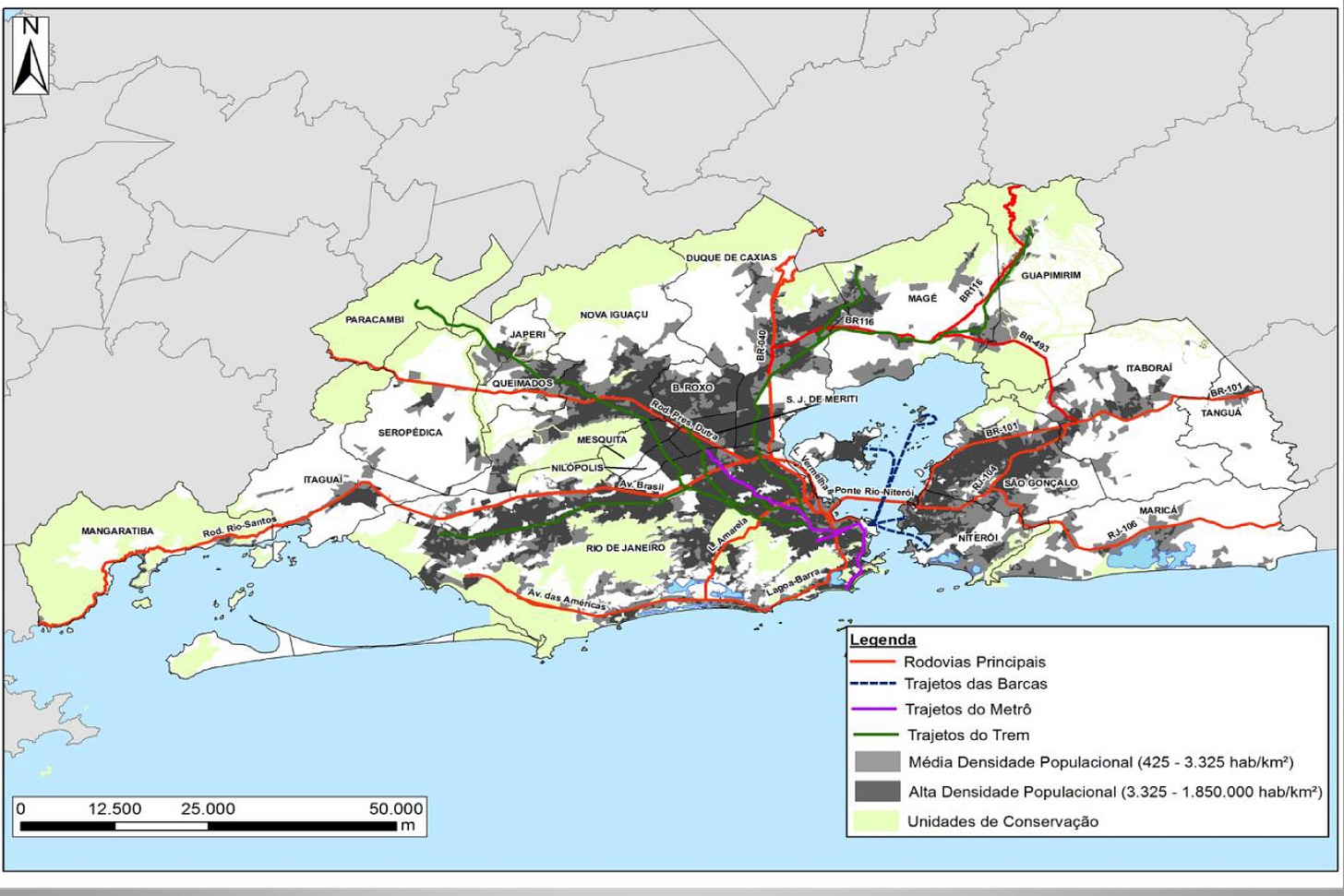

Transport corridors and population density. Source: Plano Diretor de Transporte da Região Metropolitana do Rio de Janeiro.

While the conventional postcard image of Rio de Janeiro is of high-rise apartments in Copacabana and Ipanema in the Zona Sul (South Zone), this density and that of the Centro (City centre) is confined to a relatively narrow coastal strip, This area is served by the Metrô do Rio, the highest capacity and most frequent public transport mode, including the just-opened Metrô Line 4 to Barra de Tijuca. Meanwhile, high levels of density, albeit at lower heights, is widespread across the poorer Zona Norte (North Zone) and Zona Oeste (West Zone) which are only served by buses and commuter rail, as shown on the map above.

At the risk of over-simplification, the four BRT projects serve the poorer Zona Norte (North Zone) and Zona Oeste (West Zone) while the two rail projects - light rail and Metrô Line 4 - serve the more affluent Centro (City centre) and Zona Sul (South Zone).

Of the six big Olympic legacy projects, the two rail projects serving better off parts of the city absorbed the lion's share of the public expenditure at 61% while the four BRT projects serving poorer parts of the city make up the remaining 39%. However, what is missing from this is the lack of focus on the 8 million daily bus customers not on the BRT network. A small proportion of these will be will served by the two remaining BRT projects, TransOlímpica and TransBrasil, but the vast majority will not.

While the BRT projects have been useful, a key characteristic of Rio de Janeiro is intense tidal commuter flows from the Baixada Fluminense and Zona Norte (North Zone) and Zona Oeste (West Zone) to the City Centre. Only the under-construction TransBrasil BRT will directly connect to the city centre with the other projects providing connections to commuter rail and the Metro in order to access the city centre.

So while the public transport investments considered as legacy projects for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Summer Olympics are useful to a greater or lesser degree, they make only a modest contribution to the challenges of a city where the private vehicle fleet is growing by 5% per year and where public transport capacity, speed, frequency and reliability are key to enabling accessibility in a city marked by particularly pronounced extremes of wealth and poverty. The Plano Diretor de Transportes has a long shopping list of projects needed to keep Rio de Janeiro moving. Here's hoping that Rio de Janeiro builds on the useful building block of the Olympic legacy projects and focuses its investments where the need is, not where the money is.

[Note: This piece is by necessity based on reading and interpretation of publicly available information in Portuguese and English from a distance. It is a potted summary of a range of very complex transport and urban issues that defy easy solution and digestion into a single blog post. Comments welcome.]

Disclaimer: The author of the above post is an employee of Auckland Transport, however, the views, or opinions expressed in this post are personal to the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Auckland Transport, its management or employees. Auckland Transport is not responsible for, and disclaims any and all liability for the content of the article.